If you got money for Christmas, 10 Books That Screwed Up the World: and 5 Others That Didn't Help would be a good use of your dime. Therein, Ben Wiker, senior fellow at St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology, relates - among many other useful stories - the curious case of the canals on Mars.

If you got money for Christmas, 10 Books That Screwed Up the World: and 5 Others That Didn't Help would be a good use of your dime. Therein, Ben Wiker, senior fellow at St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology, relates - among many other useful stories - the curious case of the canals on Mars.Canals on Mars?

A number of prominent scientists, beginning in 1877 with Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, were convinced that they saw through their telescopes an intricate system of canals on Mars. These canals were all very geometrical and hence obviously carried water for the great Martian civilization. The certainty of intelligent life on Mars was trumpeted (with the aid of businessman and amateur astronomer Percival Lowell). Books were published. Major newspapers declared the evident certainty to the astounded (and gullible) public. Helping to whip the public into a frenzy was alien enthusiast H. G. Wells, whose War of the Worlds seared into people's minds the dire fate that awaited Earth once the Martians stopped boating around their canals and launched their inevitable attack.In describing this story, I would have used terms like "design inference" (in this case, no), inference to the best explanation, and following the evidence wherever it leads. Qualities absent from the Big (materialist) Science left over from the twentieth century.

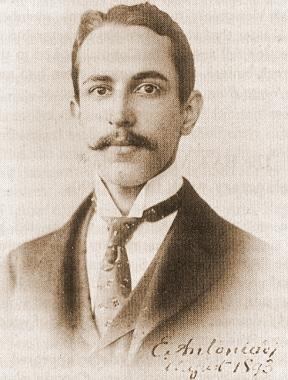

By 1930, this certainty was exploded by another astronomer, E. M. Antoniadi, who pointed out that the "canals" weren't canals; they weren't nice geometrically drawn lines of precision traced on the surface of Mars, but just fuzzy shapes.

The lesson is simple enough. Schiaparelli, Lowell, Wells, and a host of other scientists and popularizers wanted to see life on Mars. The alien enthusiasts just wanted to see what was fuzzy as straight and geometrical because they wanted Mars to be populated with aliens. It is often our desire to have something be true that makes us clearly and distinctly see the false as true, the imagined as real. This is as true in the history of science as it is in our everyday life. In either case, reality is the appropriate test of our everyday beliefs and scientific theories. (pp. 25-26)

Antoniadi was lucky, I suppose, to live when he did. He could have been a Guillermo Gonzalez, exiled to a Christian college for speaking the truth about Earth's location and qualities, in relation to the solar system. Remember that Gonzalez's key point is that Earth is an unusual planet, but the materialist agenda needs to show that there are zillions of Carl Sagan's "pale blue dots" out there.

And just now Call Display is asking me to accept a call from a planet orbiting the Alpha Centauri star system, from an alien who knows there is no mind or free will and thinks that everyone should be genetically planned and ... hey, wait a minute, buddy! Aren't you just a fundraiser for Ivy League U's? Get offa my line and get ME offa yer list!!! Sure, you people will go bankrupt before you smarten up, but you are just so not my problem!

See also: Alfred Russel Wallace on why Mars is not habitable